Neurological Emergencies

Objectives

Content coming soon...

Scope

Content coming soon...

Audience

Content coming soon...

Initial Assessment & Management

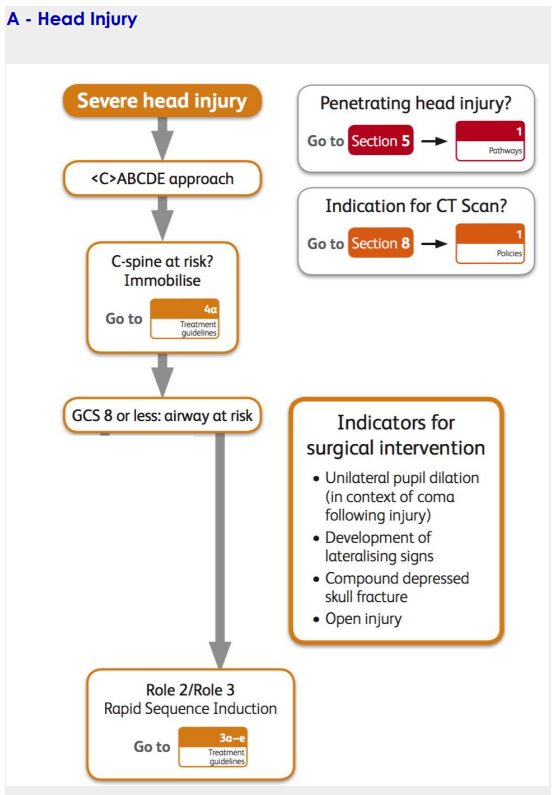

Head injuries - indications for neurosurgical referral

Criteria for urgent neurosurgical consultation are the presence of one or more of the

following:

• Fractured skull in combination with:

Either

-Confusion or other depression of the level of consciousness

Or

-Focal neurological signs

Or

-Fits

• Confusion or other neurological disturbance persisting for more than 4

hours even if there is no skull fracture

• Coma continuing after resuscitation

• Suspected open injury of the vault or the base of the skull

• Depressed fracture of the skull

• Neurological deterioration

section 5 pathways = Blood Products and Supply Pathway

section 8 = Peri-Arrest Rhythms

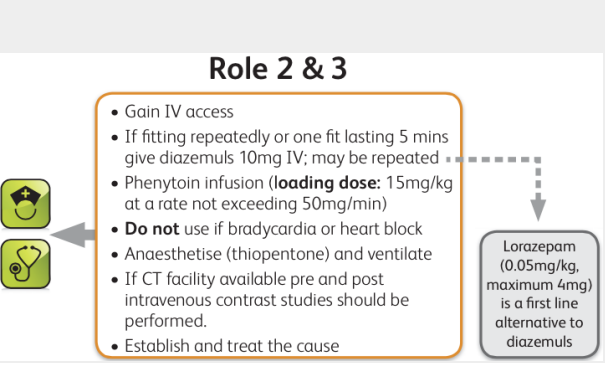

Seizures

Neurological Infection

Neurology and Fever

Issue:

Without definitive neuroimaging and CSF analysis, ability to differentiate between

meningitis and encephalitis on clinical grounds alone can be difficult.

Risk:

Failure to identify correct condition may impose treatment delay and subsequent

disability.

Recommend:

1. Merge with 9E (Neurology and fever) with 9 G (Encephalitis).

2. Rename 9D - Neurological Infection.

Advanced Assessment & Management

Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

Consider subarachnoid haemorrhage in any 'worst ever' or sudden onset

headache: "Sudden agonizing headache" is subarachnoid haemorrhage

until proven otherwise

History

• Most bleeds follow rupture of saccular ('berry') aneurysms in the Circle of

Willis.

• Patients report sudden onset and 'worst ever' headache

• Often described as 'like a blow to back of the head'

• Accompanied by neck pain, photophobia and vomiting

• May present and collapse or fits

• Drowsiness and confusion may occur

Investigation

• This may need to proceed alongside resuscitation

• Venous access and check glucose, FBC, clotting screen, U&E

• CXR may show changes of neurogenic pulmonary oedema

• ECG may demonstrate ischaemic changes

• Urgent CT head scan to detect intracranial blood (if operationally possible;

maximally sensitive within 12 hours). If CT negative, do LP to detect

xanthochromia

Treatment

• Provide adequate analgesia and antiemetic:

• - Codeine 30-60mg PO

• - Paracetamol 1g PO/IV and/or NSAID

• - Morphine titrated

• If severly agitated or combative intubate and ventilate

• Maintain MAP c.90mmHg

• Maintain normal PaO² with supplemental oxygen

• Give at least 3L maintainance fluids/24hrs IV (more if vomiting)

• Aim to evacuate to neurosurgical unit within 24 hours of haemorrhage

Further treatment options

• Nimodipine 60mg PO every 4 hours or 1mg/hr IV (not on deployed

module scale)

Stroke

Stroke

In cases of suspected ischaemic stroke, the patient's survival and functional recovery

may depend on prompt recognition and treatment

Immediate general assessment

First 10 minutes after arrival to the hospital

• Assess the airway, breathing circulation, and vital signs

• Provide oxygen by mask, obtain venous access

• Take blood samples (FBC, U7Es, coagulation studies)

• Check blood glucose (BM Stix): provide treatment if indicated

• Obtain a 12-lead ECG: check for arrhythmias

• Perform a mini-neurological assessment including Glasgow Coma Scale

Immediate Neurological Assessment

First 25 minutes after arrival to the hospital

• Review the patient's history

• Establish onset (<3 hours required for thrombolytics)

• Perform a full physical examination

• Perform a full neurological examination. Determine stroke severity

• Obtain urgent non-contrast CT scan (door-to-CT scan read civilian

performance indicator is <45 minutes after arrival)

Management

• CT scan is undertaken to rule out non-ischaemic causes of stroke (e.g.

SAH, tumour, traumatic haemorrhage)

• It CT negative, review thrombolytic exclusions and review risk and benefits

of thrombolysis therapy for patient

• If elect for thrombolytic therapy door-to treatment goal is <60 minutes

Note:

The use of thrombolytic therapy for acute ischaemic stroke is not yet

routine in UK civilian practice and the decision to use this therapy must rest

with the deployed consultant physician.

Encephalitis

Viral encephalitis

• Encephalitis means ‘inflammation of the brain’ and is usually the result of a

viral illness. There are 2 main types (i) acute viral encephalitis, and (ii)

post-infectious encephalitis (an autoimmune condition).

Symptoms

• Encephalitis may begin with a flu-like illness or headache, progressing to

confusion, drowsiness, altered level of response, fits and coma.

• Photophobia and neck stiffness may occur, as in meningitis, but symptoms

that help discriminate encephalitis include dysphasia, sensory changes, loss of

motor control and uncharacteristic behaviour.

• Some symptoms are attributable to a rise in intracranial pressure (severe

headache, dizziness, confusion and fits).

Diagnosis

• There is no useful field diagnostic test for viral encephalitis: diagnosis will

be on the clinical presentation. Polymerase chain reaction is sensitive for

diagnosing HSV-1 should blood samples be returned to UK.

Treatment

• In most cases treatment is symptomatic and is not amenable to antiviral

therapy. Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) and varicella zoster

encephalitis may respond to acyclovir 10mg/ kg IV every 8 hours. If given

in the first few days of illness the mortality can be reduced from ~80% to

~25%. Treatment may often have to be continued beyond the standard 10

day regimen (potentially for up to 21 days).

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE)

• This is caused by TBE virus (of the family Flaviviridae) and is spread by the

ixodid tick, endemic in Europe, former Soviet Union and Asia. The

incubation period is 7–14 days after which there is a 2–4 day viraemic

phase followed by a remission (of ~8 days) then a second febrile illness in

20–30% characterised by symptoms encephalitis, meningitis or both.

Treatment is symptomatic and the disease is rarely fatal (1–2%) although

sequelae are common.

Meningococcal Disease

Prolonged Casualty Care

Content coming soon...

Paediatric Considerations