This is not the live version of CGOs.

This area is for testing only.

Content coming soon...

Content coming soon...

Content coming soon...

Content coming soon...

Content coming soon...

Content coming soon...

Content coming soon...

Features (may be delayed)

• Chest pain

• Hyperinflated hemithorax

• Splayed ribs

• Extreme respiratory distress (consistent; refractory to reassurance)

• Low SpO2

• Reduced/absent breath sounds

• Hyperresonance

• Reduced/absent movement on affected side

• Late signs: hypotension; trachea deviated away from affected side;

distended neck/ chest/upper arm veins (inconsistent sign if hypovolaemia)

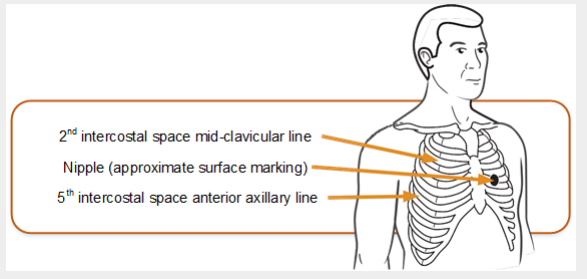

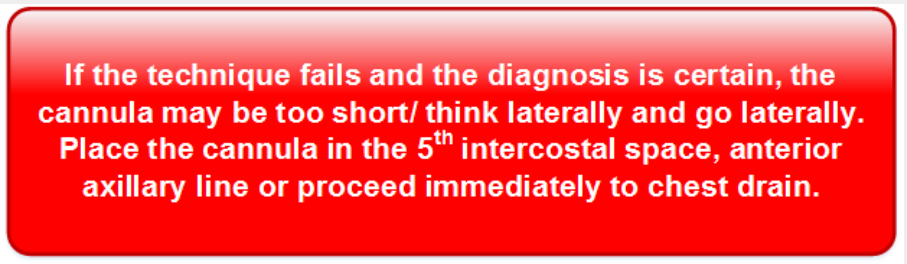

Needle decompression (affected side)

Locate second intercostal space mid-clavicular line on affected side (2nd rib joins the

sternum at the sternal angle; 2nd intercostal space is below this rib).

• Insert the needle decompression device perpendicularly into the chest, just above the

3rd rib. Air may be heard escaping.

• Secure the device in place and check the patient for signs of improvement.

• Document the procedure (this is important if the device is removed/falls out before the

casualty reaches hospital)

Definitive care

• A chest drain is required

Features (immediate)

• Low SpO2

• Hypotension

• Surgical emphysema

• High inflation pressures

• Affected side showing over-expansion (ribs splayed), reduced mobility,

reduced/absent breath sounds, increased resonance

• Late signs: trachea deviated away from affected side

• Distended neck/chest/upper arm veins (inconsistent sign if hypovolaemia)

• Potential for bilateral tension pneumothorax

Needle decompression (affected side)

Locate second intercostal space mid-clavicular line on affected side (2nd rib joins the

sternum at the sternal angle; 2nd intercostal space is below this rib).

Definitive Care

• A chest drain is required

Features

• Shock (tachycardia and hypotension)

• Affected side showing: reduced breath sounds, dullness to percussion,

under-expansion and reduced mobility

• Respiratory distress (mild – severe)

If a massive haemothorax is present, gain IV access, consider giving blood products and

TXA.

Give analgesia and antibiotics in line with DMS Deployed Antibiotic Policy

For Haemorrhagic shock:

Go to

Myocardial Infarction and Acute Coronary Syndromes ( link to NICE guideance)

Evacuate to definitive care as T1

Features

• Low SpO2

• Respiratory distress

• “Sucking” and bubbling from the wound

• Shock

• Affected side showing reduced movement, absent breath sounds, reduced

mobility (under-expansion), increased resonance

First aid

• Apply Russell Chest Seal and reassess.

• A chest drain may be required if there is a prolonged hold and an

appropriate skill set available.

• Ventilate if there is respiratory compromise despite presence of chest

drain.

For haemorrhagic shock go to:

Go to

Myocardial Infarction and Acute Coronary Syndromes ( link to NICE guideance)

Evacuate to definitive care as T1

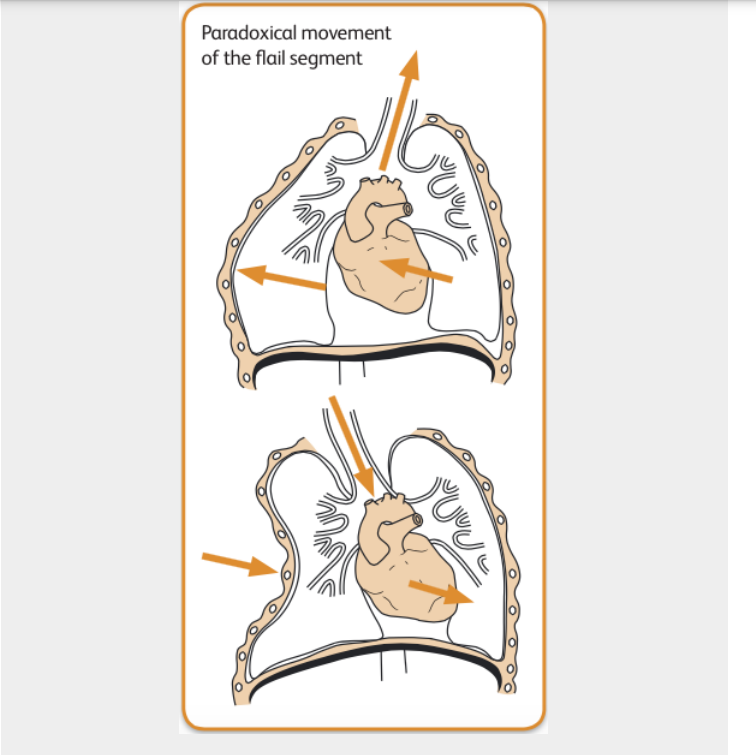

Features

• Severe chest pain

• Extreme respiratory distress

• External signs of blunt chest injury (bruising/swelling/seatbelt marks)

• Crepitus: fractured ribs/surgical emphysema

• Paradoxical movement of the flail segment (see diagram, may be subtle),

or hypomobility

• Low SpO2

• Signs from associated haemothorax may be present

Resuscitation

• Critical decision: exclude or treat associated tension (key indicator is overinflation

of hemithorax). Remember that needle decompression in absence of tension

might make the patient’s condition worse.

• A chest drain (technically may be difficult) will be needed for failed

decompression, large simple pneumothorax. There is a low threshold for postventilation chest drain because of the risk of tension pneumothorax.

• Continuing treatment is principally directed towards the underlying contusion.

Where there is respiratory compromise (hypoxia and/or hypercapnia) on blood

gases proceed to ventilation (Rapid Sequence Induction of anaesthesia by

trained staff only).

Go to: Airway Compromise

First aid

• Evacuate T1 with affected side down (will offer some splinting of segment).

BATLS resuscitation

• Critical decision: exclude or treat associated tension (key indicator is overinflation

of hemithorax). Remember that needle decompression in absence of tension

might make the patient’s condition worse.

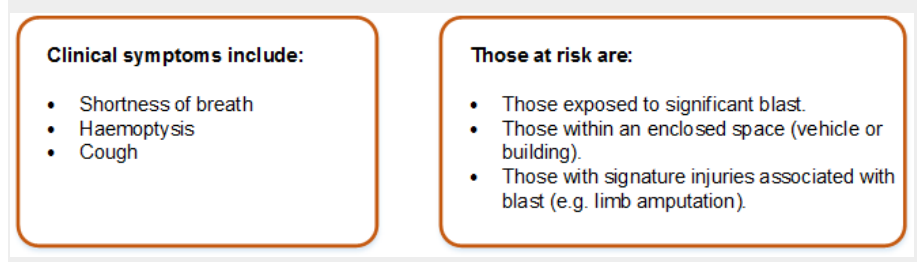

Features

• An injury where there is initially diffuse bleeding with the lung (causing

hypoxia), which progresses to an inflammatory state with the lung.

• Blast Lung Hypoxia can get rapidly worse: or develop over 24-48 hours.

• Small number of these patients present with severe refractory hypoxia very

soon after injury

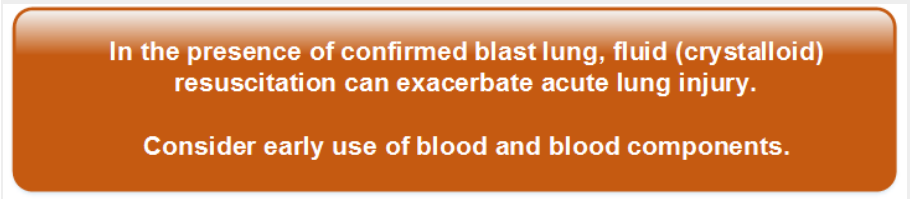

Guidance for Management • Initial resuscitation follows standard DMS ABC protocol. − Give high flow oxygen to maintain SaO2 over 95%. • Actively exclude pneumothorax and haemothorax.

Features

• Pneumothorax may occur spontaneously in the absence of trauma.

• Pneumothorax may also be secondary to asthma, pneumonia or TB.

• Sudden onset unilateral pleuritic chest pain

• Dyspnoea +/– cough.

• Depending on size of pneumothorax there may be tachypnoea and

tachycardia and percussion may be normal or hyperresonant.

Investigations

• CXR is essential to diagnose small pneumothoraces: the stethoscope is only a

crude diagnostic aid.

• Monitor SpO2.

• Measure ABG when there is dyspnoea and/or reduced SpO2.

• ECG when the prominent symptom is chest pain.

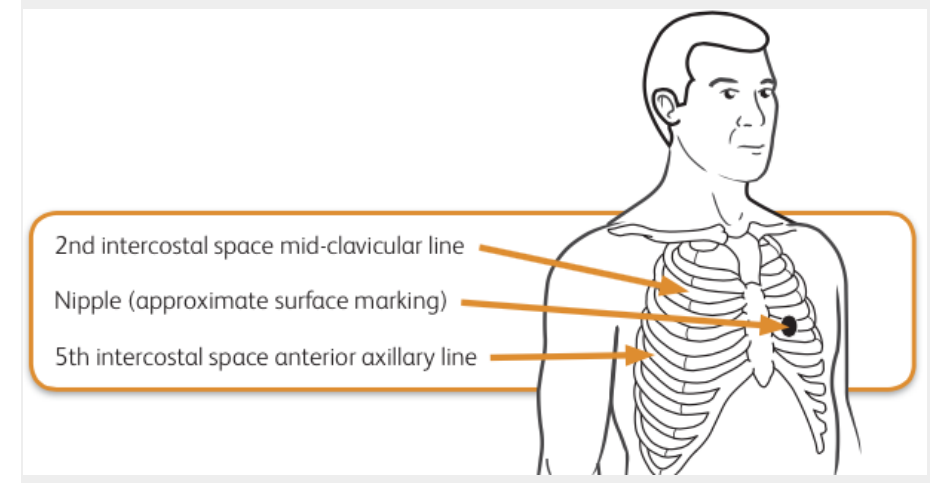

Treatment

• Aspiration is recommended for spontaneous pneumothorax:

– infiltrate with local anaesthetic, insert a 16G IV cannula in the 2nd intercostal

space

in the mid clavicular line

– attach three way tap and aspirate with a 50ml syringe

– continue aspiration until patient coughs excessively or until 2.5 litres of air is

removed.

• If aspiration unsuccessful insert a chest drain.

Where no chest X-ray capability is available, the patient is symptomatic

and clinically there is a pneumothorax, insert a chest drain

Note

Ultrasound can be used successfully to detect a pneumothorax.

Venous thromboembolic (VTE) disease (deep vein thrombosis, DVT, +/–

pulmonary embolic disease, PED), is a major contributor to morbidity and

mortality in hospital admissions across all specialities. Studies have shown

that 0.9% of all hospital admissions will die of PED, 10% of all hospital deaths

are due to PED and the risk of VTE rises tenfold in patients hospitalised after

trauma, surgery or immobilising medical illness.

• VTE thromboprophylaxis is to be given unless there is a clear indication to the

contrary. The decision NOT to give prophylaxis should be made by a senior

clinician and reasons for this decision recorded in the clinical notes.

Notes

• Below-knee GECS are NOT to be used

• LMWH does not require coagulation monitoring

• Aspirin not suitable for prophylaxis as of unproven efficacy

• Duration of therapy is until fully mobile or discharge from hospital