Sexual Health

Initial Assessment & Management

Introduction

• Maintaining sexual health is a normal and important part of life.

• It is common to see genitourinary infections on deployment, which can be

both sexually transmitted and non-sexually transmitted. This may be

infection that individuals have acquired before deploying, conditions

acquired whilst on deployment or reactivation of infection.

• Most conditions can be managed without evacuation and specific guidance

is given within these CGOs on individual conditions including when to refer.

• For the specific conditions that do require evacuation, ensure discussion

with the Military Advice and Sexual Health/HIV service (MASHH) to decide

on the timing for evacuation and how to manage the patient whilst awaiting

transfer.

• Many healthcare professionals within DPHC have accredited Sexual Health

training, having completed the Sexually Transmitted Infections Foundation

course (STIF) but if there is no-one who is STIF-trained, investigation and

management can still be completed by a medical officer (MO) with advice

from MASHH using the contact details below.

• Basic health promotion advice is always useful and may prevent infection

occurring in the first place. This includes advice on using condoms

(providing condoms, checking technique and demonstrating use), and

regular sexual health testing.

• R1 Sexual Health CGOs are relevant to Medics, Nurses and

Doctors. Ensure you know your clinical competencies when

using this guide and consult a senior clinician if cases are

beyond your scope of practice.

• If queries remain after discussing with a senior clinician or

SMO, seek further advice from MASHH Reach back service

(available 24/7) on:Mobile: 07929 788873

Pando App (DMS Network) using ‘MASHH Ask Advice’

Complete Sexual Health screening wherever possible. If not

immediately available, arrange for testing at the next

available opportunity

• MOs and trained nurses: For intimate examinations, always

offer a chaperone and record if the patient declines

• There are many relevant Patient Information Leaflets and

advice available for Sexual Health conditions from the

British Association for Sexual Health/HIV on www.bashh.org

Emergency Contraception

1. This CGO covers oral Emergency Hormonal Contraception.

2. Although the Copper Intrauterine Device (IUD) is the most effective method of

Emergency Contraception (EC) and should be offered to all women who have had

Unprotected Sexual Intercourse (UPSI) and who do not want to conceive, it is unlikely

that this will be available in an operational deployment setting. The Copper IUD can be

inserted for EC within 5 days after the first UPSI in a cycle or within 5 days of the earliest

estimated date of ovulation, whichever is later (i.e. up to Day 19 of a 28-day cycle). If this

method is available with a trained clinician, discuss with MASHH. If not available or the

patient does not want this, follow the guidance below for Emergency Hormonal

Contraception.

3. Women who do not wish to conceive should be offered EC after Unprotected Sexual

Intercourse (UPSI):

a. that has taken place on any day of a natural menstrual cycle

b. from Day 21 after childbirth

c. from Day 5 after an abortion, miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy

d. if their regular contraception has been compromised or used incorrectly

4. Information provided to patient.

a. The copper IUD is the most effective method of EC and reasons why this may not

be available (if it is available, give oral EC at the time and then refer for Copper IUD in

the required timeframe)

b. Oral EC methods do not provide contraceptive cover for any UPSI that takes

place after oral EC given

c. Ulipristal Acetate Emergency Contraception (UPA-EC) is effective for EC up to 120

hours after UPSI and is more effective than LNG-EC

d. Levonorgestrel Emergency Contraception (LNG-EC) is licensed for EC up to 72

hours after UPSI (it is ineffective if taken more than 96 hours after UPSI)

e. Oral EC given after ovulation is likely to be ineffective

f. Higher weight or higher BMI may reduce the effectiveness of oral EC (especially

LNG-EC)

g. Ongoing Contraception will be required to avoid any further risk of pregnancy (give

women information on all methods and how to access these)

5. Reach back to SMO or MASHH

a. If oral EC has already been used in the same cycle

b. If the patient has taken progestogens in the last 7 days (UPA-EC may be less

effective)

c. If the patient is using any enzyme-inducing drugs

d. How to quick start ongoing hormonal contraception if oral EC is used

e. Contraindications for giving oral EC

f. Advice for breastfeeding women given UPA-EC.

Sexual Assault

1. This CGO outlines the pathway for the management of individuals who

present following a sexual assault on operations. Clinicians may also be

involved with the management of individuals from local communities or other

areas of responsibility. If a sexual assault occurs on firm base, seek

immediate advice from a senior clinician and refer to local services such as a

Sexual Assault Referral Centre (SARC).

2. Seek immediate advice from Military Police when there is a requirement for

forensic testing. Discuss this with the individual and document it in the

attendance record.

3. The initial priorities for an alleged victim of a sexual offence are providing first

aid and treating any injuries sustained. A police investigation may run

concurrently and attention must be paid to the early preservation of evidence,

however the medical management of the individual must take precedence.

4. If a forensic examination is required, Military Police will provide the correct

examination kits. The forensic examination is only performed in the

appropriate clinical environment by appropriately trained personnel – this is

likely to be the most senior clinician (for example, the SMO), however it may

be the Medical Officer available. Discuss with the SMO and military police.

5. If awaiting forensic examination, provide immediate advice to victims

regarding the preservation of forensic evidence. Discourage victims from

anything that may destroy DNA evidence, e.g. using the lavatory, discarding

underwear or sanitary products, washing, showering, bathing, washing hands,

removing/washing/discarding/destroying any clothing, drinking, eating,

cleaning teeth, or smoking. If individuals need to use the lavatory, they can

place all soiled products (e.g. sanitary products) into a clean plastic bag and

collect urine/faces in a clean container.

6. It is essential to be sensitive and responsive to the individual’s needs and

wishes, and to recognise that sexual assault happens to males and females of

any age. It can be recent or historical.

7. Where required, appropriate services and support should be offered, taking

into account all clinical, psychological and welfare needs.

8. Please see the algorithm below for sexual assault management.

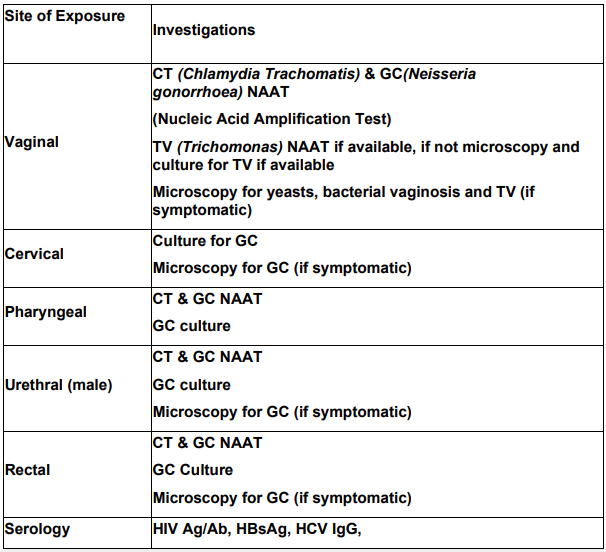

The examination should only be conducted by an MO or trained nurse able to take SH

samples. This may be conducted by the FME after the forensic sampling has taken

place.

Refer for investigations if not available.

Other tests may be offered dependant on symptoms e.g. Herpes simplex virus

(HSV) PCR

Resources:

1. JSP950 Leaflet 7-2-1 Guidance on risk assessment and immediate

management of needle stick/sharps/blood/body fluid and tissue exposure

incidents

2. JSP 839 Victim Services Annex B Guidance to Commanding Officers and

Victims when dealing with allegations of serious criminal offences including

sexual offences.

3. UK Guideline for the use of HIV Post-Exposure Prophylaxis 2021.

BASHH/BHIVA/NICE. Access via www.bashh.org/guidelines

4. JFSp(ME) SOI 060 – Management Guidelines for a patient presenting to

medical services with an allegation of sexual offence.

5. Management of adult and adolescent complainants of sexual assault 2012

BASHH NICE

HIV

Management of Conflict Related Sexual Violence

This CGO provides guidance on the principles, management, treatment and onward

referral of survivors of Conflict Related Sexual Violence (CRSV) to the appropriate

Medical Treatment Facility (MTF) and to ensure we Do No Harm.

For management of Sexual Assault involving Armed Forces personnel, refer to Sexual

Assault guidelines

1. What is Conflict Related Sexual Violence (CRSV)?

a. CRSV describes sexual violence in conflict settings. It includes rape or sexual assault

(non-consensual penetration of the vulva, mouth or anus using a penis, other body part or an

object), sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortions, enforced

sterilisations, enforced marriages and sexual exploitation and trafficking.

b. CRSV also includes sexual violence used as a deliberate military strategy

(defined as a War Crime under International Law).

c. In humanitarian settings, conflict-related or natural humanitarian crises can lead to

mass displacement and the breakdown of social protections. This increases the risk,

particularly for women and children who are refugees or internally displaced persons

(IDPs).

2. When should the Defence Medical Service (DMS) become involved?

a. DMS should treat all life, limb and sight-threating injuries regardless of

nationality

b. DMS must not routinely provide clinical care to civilian victims and other individuals

not included in the medical rules of engagement (MROE) whilst deployed on Operations

when other organisations and MTFs are available. These include Host-Nation facilities

and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs)

To respond when there are other appropriate actors in situ would potentially DO

HARM

c. There may be situations where the DMS are the only MTFs operating or where other

organisations are either inaccessible or unable to provide first-line treatment. In

extremis, the DMS must be prepared to respond to survivors until transfer and referral

to another appropriate MTF is available

d. When there are no other organisations available, the potential to DO HARM still

remains and involvement by the Military should only be at the victim’s request

e. Forensic/Biological evidence:

f. DMS should not collect biological or forensic evidence as routine. Seek advice

from Legal and MP at the earliest opportunity if this is required

If the survivor/perpetrator is from an Armed Force (or Partner Nation), evidence

could be collected with patient consent using MP held FME kit by trained

personnel (seek advice from MP and see Sexual Assault guidelines

3. Principles in Management

Ensure a compassionate response, always treating the survivor with dignity and respect.

Male Urethritis

1. Urethritis is inflammation of the urethra. Clinical features include urethral discharge

(discharge from the end of the penis) and dysuria (pain when urinating). This is seen

almost exclusively in men.

2. The most common causes of Urethritis are Gonorrhoea (Neisseria Gonorrhoeae) and

Chlamydia (Chlamydia Trachomatis) although there are other organisms that can cause

this. Urethritis is also caused by anything that causes inflammation in the urethra, e.g.

trauma, inadequate hydration, excessive supplements/shakes.

3. A detailed history is essential to assess the possible cause of urethritis. Abnormal

discharge should be confirmed by performing a clinical examination. Examination and

investigation are very important to ensure the key diagnoses are treated properly.

4. In men complaining of dysuria (pain urinating), refer to an MO or trained nurse for

examination as above for urethral discharge.

Resources:

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV Guidelines for vaginal discharge.

Accessed via

https://www.bashh.org/guidelines

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Accessed

via https://cks.nice.org.uk/vaginal-discharge

Vaginal Discharge

1. Vaginal discharge is a natural phenomenon in females of reproductive age and is a

white/clear, non-smelly discharge that changes with the menstrual cycle. It is thick and

sticky for most of the cycle but becomes more transparent and stretchy for a short time

around ovulation. Normal vaginal discharge can also be altered by pregnancy, sexual

stimulation, contraceptive use, and age.

2. Abnormal vaginal discharge is characterised by a change in the normal discharge, i.e.

change in colour, consistency, volume and/or smell. It can also be associated with other

symptoms such as itch, soreness, lower abdominal/pelvic pain, pain passing urine and

abnormal bleeding such as bleeding after sex or in-between periods.

3. The most common causes of abnormal vaginal discharge are:

• A change in the environment of the vagina (e.g. Bacterial Vaginosis or

Vaginal Candidiasis)

• Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) such as Chlamydia, Gonorrhoea

and Trichomonas Vaginalis

• Non-infective causes such as a retained foreign body (e.g. a retained

tampon), inflammation due to allergy or irritation, cervical polyps or erosion,

or tumours.

4. A detailed history is essential to assess the possible cause of an abnormal discharge.

Refer to a MO or trained nurse where an examination is required to ensure there are no

missed diagnoses. If this is not possible due to the deployed environment, discuss with a

senior clinician or MASHH to ensure best management and follow-up testing where

required.

5. If any lower abdominal pain/unwell/abnormal appearance of cervix - perform a

pregnancy test and discuss with SMO or MASHH.

Resources:

Resources:

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV Guidelines for vaginal discharge.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Accessed

Genital Lumps

1. Genital lumps can be caused by genital warts (Human Papilloma Virus, HPV) or

molluscum (a pox virus). However, any skin condition can appear on the genitals. It is

therefore essential to complete a general skin examination.

2. Use the algorithm below.

Resources:

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV Guidelines for Anogenital Warts,

Molluscum Contagiosum.

Accessed via https://www.bashh.org/guidelines

Genital Ulcers

1. Genital ulcers can be caused by Herpes Simplex virus (HSV) which is a very common

virus. It is a controllable condition, so it is essential to diagnose and give the appropriate

information and management.

2. Examine patients presenting with symptoms and look for other clinical signs which

may indicate other conditions, e.g. Syphilis, which can also present in the first stage as a

genital ulcer. This is more common in MSM (men who have sex with men). Discuss with

MASHH if there is any suspicion of Syphilis.

Resources:

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV Guidelines for Anogenital Herpes.

Accessed via